St. Nicholas – His Legend and His Role in the Christmas Celebration and Other Popular Customs (By George H. McKnight, 1917) – Chapter 3

CHAPTER III

THE BOY ST. NICHOLAS AND ST. NICHOLAS THE PATRON SAINT OF SCHOOLBOYS

The legendary story of St. Nicholas has certain features that distinguish it from the legendary stories of other saints. The story of St. Nicholas is not a narrative of a single dramatic achievement, like that in the life of St. George, nor of a glorious martyrdom, like that of a St. Sebastian or a St. Cecilia. Nor is the name of St. Nicholas associated with the diffusion of the Christian faith like that of St. Augustine, St. Boniface, or St. Patrick, nor with the exposition of Christian doctrine, like that of St. Jerome or St. Bernard. More like, it is yet different from, that story of perfect exemplification of the Christian life, the life story of St. Francis. The story of St. Nicholas consists almost entirely of a series of beneficent deeds, of aid afforded humanity in distress, accomplished either by St. Nicholas during his lifetime or through his intervention after death. As a benefactor he ranks almost with Divinity in his aid rendered, and even lacks the severity of the justice that attends Divine awards.

The conception of St. Nicholas, then, is almost that of beneficence incarnate. The minor traits of his personality, however, the nature of his parentage, the time details in his life history, the exact manner of his death, are left in comparative obscurity. The very vagueness of the information concerning him serves in great measure to explain the remarkable variety of the rôles he has assumed in the world’s history. Only the nebulous ideas that have prevailed concerning him have made it possible that in Scandinavia his name should be connected with that of a hostile water demon, known in English as the “Old Nick,” while in certain parts of Siberia he receives divine honor and is worshiped as the “Russian god Nicolo.” A similar reason explains how he comes to be regarded as patron saint of classes of people as dissimilar as schoolboys, parish clerks, unwedded maids, seamen, pirates, and thieves, how it is possible to associate him with the whimsical children’s friend Santa Claus.

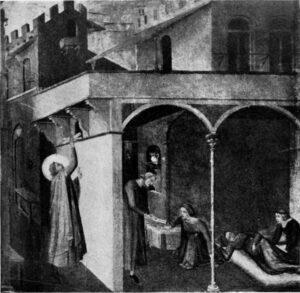

Beato Angelico. Three Scenes from the Early Life of St. Nicholas.

The story of the boyhood of St. Nicholas, reverent in tone and not a little tinged with the supernatural, is of the kind that one might well look for in the legendary account of one whose memory is entirely associated with kindness and generosity. St. Nicholas was born, the Golden Legend tells us, ‘in the city of Patras in Asia Minor, of rich and holy kin. His father was Epiphanes, and his mother Johane. He was begotten in the first flower of their age, and from that time forthon they lived in continence and led an heavenly life.’ From the first the boy Nicholas manifested signs of extreme piety, observing fasting periods even in earliest infancy. The story runs: “Then, the first day that he was washed and bained, he addressed himself right up in the bason, and he would not take the breast nor the pap but once on Wednesday and once on Friday, and in his young age he eschewed the plays and japes of other young children. He used and haunted gladly holy church; and all that he might understand of holy scripture, he executed it in deed and work after his power.” Thus he is represented in the narrative of the Golden Legend. Thus too he is represented in the series of scenes painted by Beato Angelico and preserved in the Vatican gallery. In these interesting paintings there is a scene representing the infant Nicholas at the time of his birth standing up in the basin, and a second scene where he is represented in a flower-covered ground in front of a church, devoutly standing in front of a group of worshipers listening to the words of a bishop who preaches from above in an outside pulpit. Chaucer’s Prioress, speaking of the saintly boy murdered by the Jews, remarks:

It is not hard to see why he should have been chosen as patron saint of children, unless, indeed, the story of his pious childhood itself originates from the fact that he was the patron saint of children. In the words of the English Liber Festivalis, “his parents called him Nycolas, that is a mannes name, but he kepeth the name of a child, for he chose to kepe vertue, meknes, and simplenes, and without malice…. And therefore, children don him worship before all other saints.”

But it is to be feared that the exemplary boyhood of St. Nicholas would hardly in itself have sufficed to give him so firm a hold on the affections of children. Children of our day, or shall we say of the day that has just passed, in the stories provided them, not infrequently read of boys almost equally exemplary, without being unduly moved to love, reverence, or emulation. A more sure road to the affections of children is through benefits received or at least stories of benefits rendered. Children love and honor St. Nicholas because they conceive of the spirit of St. Nicholas as a guardian angel, not only looking after their safety and well-being, but bringing them substantial rewards, and many of the stories told of him, led children to feel toward him the warmest gratitude and at the same time to look to him as a semi-divine protector in time of trouble.

St. Nicholas was particularly the patron saint of schoolboys, and one of the best known of the stories of protection afforded by him is thus told in the Golden Legend:

A man, for the love of his son, that went to school for to learn, hallowed, every year, the feast of S. Nicholas much solemnly. On a time it happed that the father had to make ready the dinner, and called many clerks [schoolboys] to this dinner. And the devil came to the gate in the habit of a pilgrim for to demand alms; and the father anon commanded his son that he should give alms to the pilgrim. He followed him as he went for to give him alms, and when he came to the quarfox the devil caught the child and strangled him. And when the father heard this he sorrowed much strongly and wept, and bare the body into his chamber, and began to cry for sorrow, and say: Bright sweet son, how is it with thee? S. Nicholas, is this the guerdon that ye have done to me because I have so long served you? And as he said these words, and other semblable, the child opened his eyes, and awoke like as he had been asleep, and arose up before all, and was raised from death to life.

The clerks assembled at the dinner in honor of St. Nicholas, the devil in pilgrim guise seeking alms at the door, and later strangling the boy who has followed him outside, and the boy on the bed being brought to life through influence of his protector saint, all with entire disregard to unity of time, are represented in one of the animated scenes of the painting by Lorenzetti in Florence, in which in quaintly primitive fashion is anticipated the method of the modern motion picture.

A. Lorenzetti. The Young Clerk Strangled by the Devil at the Feast on St. Nicholas’ Eve and Brought to Life by the Saint.

Another story with St. Nicholas in his favorite rôle is thus told in the Golden Legend:

There was another rich man that by the merits of S. Nicholas had a son and called him: Deus dedit, “God gave.” And this rich man did do make a chapel of S. Nicholas in his dwelling place; and did do hallow every year the feast of S. Nicholas. And this manor was set by the land of the Agarians. This child was taken prisoner, and deputed to serve the king. The year following, and the day that the father held devoutly the feast of S. Nicholas, the child held a precious cup tofore the king, and remembered his prise, the sorrow of his friends, and the joy that was made that day in the house of his father, and began to sigh sore high. And the king demanded him what ailed him and the cause of his sighing; and he told him every word wholly. And when the king knew it, he said to him; Whatsomever thy Nicholas do or do not, thou shalt abide here with us. And suddenly there blew a much strong wind, that made all the house to tremble, and the child was ravished with the cup, and was set tofore the gate where his father held the solemnity of S. Nicholas, in such wise that they all demeaned great joy.

A variant version of this story is included in the Golden Legend. It runs as follows:

And some say that this child was of Normandy, and went oversea, and was taken by the sowdan, which made him oft to be beaten before him. And as he was beaten on a S. Nicholas day, and was set in prison, he prayed to S. Nicholas as well for the beating that he suffered, as for the great joy that he was wont to have on that day of S. Nicholas. And when he had long prayed and sighed, he fell asleep, and when he awoke he found himself in the chapel of his father, whereas much joy was made for him.

Wace, the twelfth-century author of a life of St. Nicholas in French verse, supplies the introductory part of this story only briefly alluded to in the Golden Legend version. He tells of the rich merchant of Alexandria named Getro, and his wife, Eufrosine, who have longed in vain for children. Getro hears of St. Nicholas and goes to the city where St. Nicholas lives, to seek his aid. But he finds the saint dead and on his bier. He asks for some of the saint’s clothes. These he bears as holy relics to Alexandria and erects a church for them. The next December, on St. Nicholas’ day, a son is born and receives the name Deudoné. This son is carried off by robbers and sold to the emperor, whom he serves as cup-bearer. On St. Nicholas’ day the boy weeps but is cruelly beaten for it. At the same time his father in Alexandria is praying to St. Nicholas, and on rising from prayer, finds his son, safely restored, standing before him. After that, naturally, there is no neglect to worship St. Nicholas on his festival day.

This story seems to be closely connected with the development of St. Nicholas worship in western Europe following the removal of his relics to Bari, Italy. General veneration of the saint, long popular in the East, seems to increase in the West after that event. The particular incident just recorded is followed in Wace by these words:

which may be translated, “Before this we do not find worshipers of Saint Nicholas,” and seem to indicate that the composition of Wace was connected in some way with a newly instituted church festival.

The story was one kept particularly in memory since, as remains to be seen, it formed the subject of a schoolboy play enacted by the boys on St. Nicholas’ eve. It also forms the subject of two of the scenes in fresco, possibly by Giottino, possibly by Giotto himself, as a young man, in the church of St. Francis at Assisi. The first scene in these frescoes represents a boy prisoner of a Saracen king in the act of raising a cup to his lord seated at table, when St. Nicholas, hovering above, grasps him by the hair to bear him away. The second scene represents St. Nicholas, bringing back the boy, with the cup still in his hands, and restoring him to the astonished father and mother seated at table. The scene is an animated one. The father with both arms embraces his son, and the mother stretches out her arms. A youth in the group, with clasped hands looks to heaven, and a monk, astonished, lifts his arms. Not least of all, a little dog betrays his recognition of the restored boy.

Another story of this kind is thus told in the Golden Legend:

Another nobleman prayed to S. Nicholas that he would, by his merits, get of our Lord that he might have a son, and promised that he would bring his son to the church, and would offer him a cup of gold. Then the son was born and came to age, and the father commanded to make a cup, and the cup pleased him much, and he retained it for himself, and did do make another of the same value. And they went sailing in a ship toward the church of S. Nicholas, and when the child would have filled the cup, he fell into the water with the cup and anon was lost, and came no more up. Yet nevertheless the father performed his avow, in weeping much tenderly for his son; and when he came to the altar of S. Nicholas he offered the second cup, and when he had offered it, it fell down, like as one had cast it under the altar. And he took it up and set it again upon the altar, and then yet was it cast further than tofore, and yet he took it up and remised it the third time upon the altar; and it was thrown again further than tofore. Of which thing all they that were there marvelled, and men came for to see this thing. And anon, the child that had fallen in the sea, came again prestly before them all, and brought in his hands the first cup, and recounted to the people that, anon as he was fallen in the sea, the blessed S. Nicholas came and kept him that he had none harm. And thus the father was glad and offered to S. Nicholas both the two cups.

This story is represented in one of the frescoed scenes in the Chapel of the Sacrament at Santa Croce in Florence and in the Franciscan Church at Assisi. It also forms one of the scenes carved on the Winchester baptismal font.

Fresco at S. Croce, Attributed to G. Starnina. St. Nicholas Restores to his Father the Son with the Cup lost at Sea.

Still another story in which St. Nicholas appears as the guardian angel of schoolboys, is the one dealing with the resuscitation of the three schoolboys murdered on their journey home. The story, which appears in a number of variant forms, relates how three boys, on their journey home from school, take lodging at an inn, or as some versions have it, farmhouse. In the night the treacherous host and hostess murder the boys, cut up their three bodies, and throw the pieces into casks used for salting meat. In the morning St. Nicholas appears and calls the guilty ones to task. They deny guilt, but are convicted when the saint causes the boys, sound of body and limb, to arise from the casks. This story, of repellent detail, is “not known among the Greeks, who are so devoted to St. Nicholas.” It is also not included in the Golden Legend nor in the Roman Breviary. It seems to have been one of the elements added to the legend after the development of St. Nicholas worship in the West. Its earliest record is said to be that in the French life of St. Nicholas by Wace. With the incident in the story, Wace connects the great honor paid to St. Nicholas by schoolboys. “Because,” says Wace, “he did such honor to schoolboys, they celebrate this day [Dec. 6] by reading and singing and reciting the miracles of St. Nicholas.”

Different attempts have been made to explain the origin of this, at first, repellent story. One critic finds the explanation of the story in the conventional methods of medieval art. He explains it as growing out of a misinterpretation of an illustration representing one of the incidents in the earlier story of St. Nicholas, the well-known story of the succor lent by St. Nicholas to the three officers condemned to death by Constantine. The three captives, after the manner of the Middle Ages, were supposedly represented in a tower, and in order to make the scene more visible, only the upper part of the tower was represented. Then, too, in order to bring about the desired subordination of human to divine, the medieval artist would reduce the size of tower and prisoners in relation to the intervening saint, so that the tower would become, in appearance, a cask, and the three officers, little boys. From this pictorial representation misunderstood, if we adopt this theory, arose the story of the three boys brought to life from the packing cask.

L. di Bicci (?). St. Nicholas and the Murdered Schoolboys.

Metropolitan Museum of Art

Another explanation of the story is to be found in the association, to be discussed later, between St. Nicholas and the northern water demon known as “Nix” or “Old Nick.” According to belief prevalent in northern lands, the souls of drowned people are kept by Nix in pots. When one remembers that souls were generally represented in the form of children, one may see the close analogy between the pots of the water demon and the tubs from which St. Nicholas resuscitated the schoolboys.

Mrs. Jameson has still another explanation to offer. To use her own words: “The story is sometimes treated as a religious allegory, referring to the conversion of sinners or unbelievers. In some pictures the host is represented as a demon with hoofs and claws.”

The explanations just offered, afford interesting illustration of the ingenuity of the folk-lorist but seem superfluous. The tale could hardly be improved on for the use it serves, to excite the gratitude of young schoolboys. The details, repellent perhaps to the modern adult, trained in the school of modern naturalism, are, if one stops to think, features characteristic of the world’s classic folk-tales for children. The ogre-like ferocity of the host and hostess where the boys lodged, is quite in keeping with the tone of little Red Riding Hood or of Bluebeard.

In any event we may infer popularity of this tale from its wide prevalence. The central scene of the famous story is represented among the sculptured scenes of the church of St. Nicholas at Bari, and among the frescoed scenes at Santa Croce. It is pictured on the pages of the Salisbury missal and forms the subject of several canvas paintings by early artists. Up to within recent times a picture of St. Nicholas standing by a tub from which were emerging three boys, was to be seen painted on the side of a prominent house in Amsterdam, with the inscription “Sinterklaes.” It was one of the stories dramatically presented by medieval schoolboys on St. Nicholas’ eve. Down to our own day it has continued to be the subject of a song used in the popular dances of the Faröe Islands. The youths rising from the cask became a constant symbol used in representing St. Nicholas. In the churches of Brittany, and doubtless elsewhere in France and Belgium, among the images of saints occupying places on the pillars within the church, or standing as sentinels on each side of the recessed portals, St. Nicholas is frequently to be met with, always to be recognized by his conventional pedestal formed by the tub from which are issuing the three saved boys.

F. Pesellino. St. Nicholas and the Murdered Schoolboys.

A charming version of the story appears in a French folk-song, effectively rendered by Yvette Guilbert appropriately garbed in the robes of the kindly bishop. Anatole France, too, has brought to bear on this story, his gift of paradox in a highly diverting version containing a sequel in which the innocent St. Nicholas suffers every conceivable form of injury from the three rescued boys, who prove to be incarnations of three varied forms of human depravity.

St. Nicholas, the youth of exemplary piety, we may hope inspired proper emulation on the part of schoolboys. St. Nicholas, the generous protector, and friend, we may be sure was an object of schoolboy gratitude and love. The memory of his kindly deeds was kept alive not only in recited story, but in carved stone and painted wall. The boys themselves sang about them in beloved songs and enacted them in spirited plays. But the beneficence of the kindly saint was not confined to the past. The gifts mysteriously bestowed on the saint’s festival eve have kept alive the feelings of gratitude, and through the centuries boys have continued to look to St. Nicholas for aid and protection. “St. Nicholas be thy speed,” facetiously remarks Launce, to Speed who is about to give an exhibition of his ability to read. Even in his athletics the English schoolboy has continued to invoke the assistance of his patron saint. According to Brand, if a boy is pursued and about to be caught, the cry of Nic’las entitles him to a suspension of the play for a moment. Or if he is not ready, or is obliged to stop, to fasten his shoe or make other readjustment, the same magic word affords him protection. One is reluctant to associate St. Nicholas with the methods, not always above question, sometimes used by the athlete in order to gain time or wind, but this continued use of the name of Nicholas in sports bears eloquent testimony to the place their saint has occupied in the hearts of schoolboys.

A. Lorenzetti. St. Nicholas Providing the Dower for the Three Maidens.

1 Response

[…] St. Nicholas – Chapter 3 […]