The Evil Eye of Sani (Folk-Tales of Bengal, 1912) by Rev. Lal Behari Day

Once upon a time Sani, or Saturn, the god of bad luck, and Lakshmi, the goddess of good luck, fell out with each other in heaven. Sani said he was higher in rank than Lakshmi, and Lakshmi said she was higher in rank than Sani. As all the gods and goddesses of heaven were equally ranged on either side, the contending deities agreed to refer the matter to some human being who had a name for wisdom and justice. Now, there lived at that time upon earth a man of the name of Sribatsa,1 who was as wise and just as he was rich. Him, therefore, both the god and the goddess chose as the settler of their dispute. One day, accordingly, Sribatsa was told that Sani and Lakshmi were wishing to pay him a visit to get their dispute settled. Sribatsa was in a fix. If he said Sani was higher in rank than Lakshmi, she would be angry with him and forsake him. If he said Lakshmi was higher in rank than Sani, Sani would cast his evil eye upon him. Hence he made up his mind not to say anything directly, but to leave the god and the goddess to gather his opinion from his action. He got two stools made, the one of gold and the other of silver, and placed them beside him. When Sani and Lakshmi came to Sribatsa, he told Sani to sit upon the silver stool, and Lakshmi upon the gold stool. Sani became mad with rage, and said in an angry tone to Sribatsa, “Well, as you consider me lower in rank than Lakshmi, I will cast my eye on you for three years; and I should like to see how you fare at the end of that period.” The god then went away in high dudgeon. Lakshmi, before going away, said to Sribatsa, “My child, do not fear. I’ll befriend you.” The god and the goddess then went away.

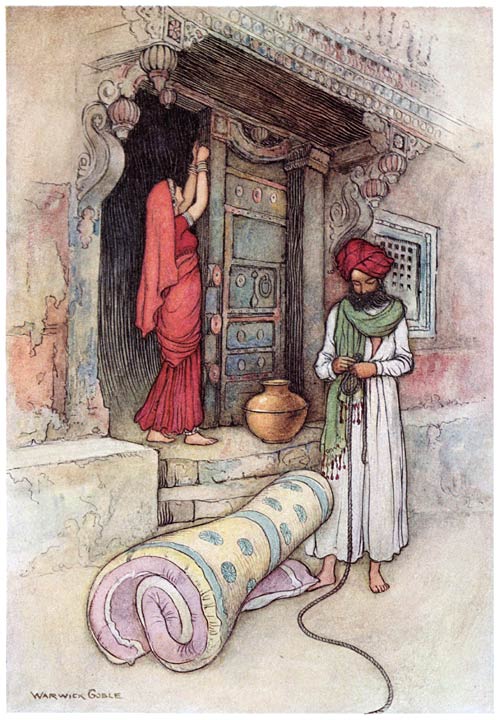

Sribatsa said to his wife, whose name was Chintamani, “Dearest, as the evil eye of Sani will be upon me at once, I had better go away from the house; for if I remain in the house with you, evil will befall you and me; but if I go away, it will overtake me only.” Chintamani said, “That cannot be; wherever you go, I will go, your lot shall be my lot.” The husband tried hard to persuade his wife to remain at home; but it was of no use. She would go with her husband. Sribatsa accordingly told his wife to make an opening in their mattress, and to stow away in it all the money and jewels they had. On the eve of leaving their house, Sribatsa invoked Lakshmi, who forthwith appeared. He then said to her, “Mother Lakshmi! as the evil eye of Sani is upon us, we are going away into exile; but do thou befriend us, and take care of our house and property.” The goddess of good luck answered, “Do not fear; I’ll befriend you; all will be right at last.” They then set out on their journey. Sribatsa rolled up the mattress and put it on his head. They had not gone many miles when they saw a river before them. It was not fordable; but there was a canoe there with a man sitting in it. The travellers requested the ferryman to take them across. The ferryman said, “I can take only one at a time; but you are three—yourself, your wife, and the mattress.” Sribatsa proposed that first his wife and the mattress should be taken across, and then he; but the ferryman would not hear of it. “Only one at a time,” repeated he; “first let me take across the mattress.” When the canoe with the mattress was in the middle of the stream, a fierce gale arose, and carried away the mattress, the canoe, and the ferryman, no one knows whither. And it was strange the stream also disappeared, for the place, where they saw a few minutes since the rush of waters, had now become firm ground. Sribatsa then knew that this was nothing but the evil eye of Sani.

“They then set out on their journey”

Sribatsa and his wife, without a pice in their pocket, went to a village which was hard by. It was dwelt in for the most part by wood-cutters, who used to go at sunrise to the forest to cut wood, which they sold in a town not far from the village. Sribatsa proposed to the wood-cutters that he should go along with them to cut wood. They agreed. So he began to fell trees as well as the best of them; but there was this difference between Sribatsa and the other wood-cutters, that whereas the latter cut any and every sort of wood, the former cut only precious wood like sandal-wood. The wood-cutters used to bring to market large loads of common wood, and Sribatsa only a few pieces of sandal-wood, for which he got a great deal more money than the others. As this was going on day after day, the wood-cutters through envy plotted together, and drove away from the village Sribatsa and his wife.

The next place they went to was a village of weavers, or rather cotton-spinners. Here Chintamani, the wife of Sribatsa, made herself useful by spinning cotton. And as she was an intelligent and skilful woman, she spun finer thread than the other women; and she got more money. This roused the envy of the native women of the village. But this was not all. Sribatsa, in order to gain the good grace of the weavers, asked them to a feast, the dishes of which were all cooked by his wife. As Chintamani excelled in cooking, the barbarous weavers of the village were quite charmed by the delicacies set before them. When the men went to their homes, they reproached their wives for not being able to cook so well as the wife of Sribatsa, and called them good-for-nothing women. This thing made the women of the village hate Chintamani the more. One day Chintamani went to the river-side to bathe along with the other women of the village. A boat had been lying on the bank stranded on the sand for many days; they had tried to move it, but in vain. It so happened that as Chintamani by accident touched the boat, it moved off to the river. The boatmen, astonished at the event, thought that the woman had uncommon power, and might be useful on similar occasions in future. They therefore caught hold of her, put her in the boat, and rowed off. The women of the village, who were present, did not offer any resistance as they hated Chintamani. When Sribatsa heard how his wife had been carried away by boatmen, he became mad with grief. He left the village, went to the river-side, and resolved to follow the course of the stream till he should meet the boat where his wife was a prisoner. He travelled on and on, along the side of the river, till it became dark. As there were no huts to be seen, he climbed into a tree for the night. Next morning as he got down from the tree he saw at the foot of it a cow called a Kapila-cow, which never calves, but which gives milk at all hours of the day whenever it is milked. Sribatsa milked the cow, and drank its milk to his heart’s content. He was astonished to find that the cow-dung which lay on the ground was of a bright yellow colour; indeed, he found it was pure gold. While it was in a soft state he wrote his own name upon it, and when in the course of the day it became hardened, it looked like a brick of gold—and so it was. As the tree grew on the river-side, and as the Kapila-cow came morning and evening to supply him with milk, Sribatsa resolved to stay there till he should meet the boat. In the meantime the gold-bricks were increasing in number every day, for the cow both morning and evening deposited there the precious article. He put the gold-bricks, upon all of which his name was engraved, one upon another in rows, so that from a distance they looked like a hillock of gold.

Leaving Sribatsa to arrange his gold-bricks under the tree on the river-side we must follow the fortunes of his wife. Chintamani was a woman of great beauty; and thinking that her beauty might be her ruin, she, when seized by the boatmen, offered to Lakshmi the following prayer——“O Mother Lakshmi! have pity upon me. Thou hast made me beautiful, but now my beauty will undoubtedly prove my ruin by the loss of honour and chastity. I therefore beseech thee, gracious Mother, to make me ugly, and to cover my body with some loathsome disease, that the boatmen may not touch me.” Lakshmi heard Chintamani’s prayer; and in the twinkling of an eye, while she was in the arms of the boatmen, her naturally beautiful form was turned into a vile carcase. The boatmen, on putting her down in the boat, found her body covered with loathsome sores which were giving out a disgusting stench. They therefore threw her into the hold of the boat amongst the cargo, where they used morning and evening to send her a little boiled rice and some water. In that hold Chintamani had a miserable life of it; but she greatly preferred that misery to the loss of chastity. The boatmen went to some port, sold the cargo, and were returning to their country when the sight of what seemed a hillock of gold, not far from the river-side, attracted their attention. Sribatsa, whose eyes were ever directed towards the river, was delighted when he saw a boat turn towards the bank, as he fondly imagined his wife might be in it. The boatmen went to the hillock of gold, when Sribatsa said that the gold was his. They put all the gold-bricks on board their vessel, took Sribatsa prisoner, and put him into the hold not far from the woman covered with sores. They of course immediately recognised each other, in spite of the change Chintamani had undergone, but thought it prudent not to speak to each other. They communicated their ideas, therefore, by signs and gestures. Now, the boatmen were fond of playing at dice, and as Sribatsa appeared to them from his looks to be a respectable man, they always asked him to join in the game. As he was an expert player, he almost always won the game, on which the boatmen, envying his superior skill, threw him overboard. Chintamani had the presence of mind, at that moment, to throw into the water a pillow which she had for resting her head upon. Sribatsa took hold of the pillow, by means of which he floated down the stream till he was carried at nightfall to what seemed a garden on the water’s edge. There he stuck among the trees, where he remained the whole night, wet and shivering. Now, the garden belonged to an old widow who was in former years the chief flower-supplier to the king of that country. Through some cause or other a blight seemed to have come over her garden, as almost all the trees and plants ceased flowering; she had therefore given up her place as the flower-supplier of the royal household. On the morning following the night on which Sribatsa had stuck among the trees, however, the old woman on getting up from her bed could scarcely believe her eyes when she saw the whole garden ablaze with flowers. There was not a single tree or plant which was not begemmed with flowers. Not understanding the cause of such a miraculous sight, she took a walk through the garden, and found on the river’s brink, stuck among the trees, a man shivering and almost dying with cold. She brought him to her cottage, lighted a fire to give him warmth, and showed him every attention, as she ascribed the wonderful flowering of her trees to his presence. After making him as comfortable as she could, she ran to the king’s palace, and told his chief servants that she was again in a position to supply the palace with flowers; so she was restored to her former office as the flower-woman of the royal household. Sribatsa, who stopped a few days with the woman, requested her to recommend him to one of the king’s ministers for a berth. He was accordingly sent for to the palace, and as he was at once found to be a man of intelligence, the king’s minister asked him what post he would like to have. Agreeably to his wish he was appointed collector of tolls on the river. While discharging his duties as river toll-gatherer, in the course of a few days he saw the very boat in which his wife was a prisoner. He detained the boat, and charged the boatmen with the theft of gold-bricks which he claimed as his own. At the mention of gold-bricks the king himself came to the river-side, and was astonished beyond measure to see bricks made of gold, every one of which had the inscription—Sribatsa. At the same time Sribatsa rescued from the boatmen his wife, who, the moment she came out of the vessel, became as lovely as before. The king heard the story of Sribatsa’s misfortunes from his lips, entertained him in a princely style for many days, and at last sent him and his wife to their own country with presents of horses and elephants. The evil eye of Sani was now turned away from Sribatsa, and he again became what he formerly was, the Child of Fortune.

Thus my story endeth,

The Natiya-thorn withereth, etc.

If you liked this story, leave me a comment down below. Join our Facebook community. And don’t forget to Subscribe!

Enjoy other folk tales from India!