The Story of the Rakshasas (Folk-Tales of Bengal, 1912) by Rev. Lal Behari Day

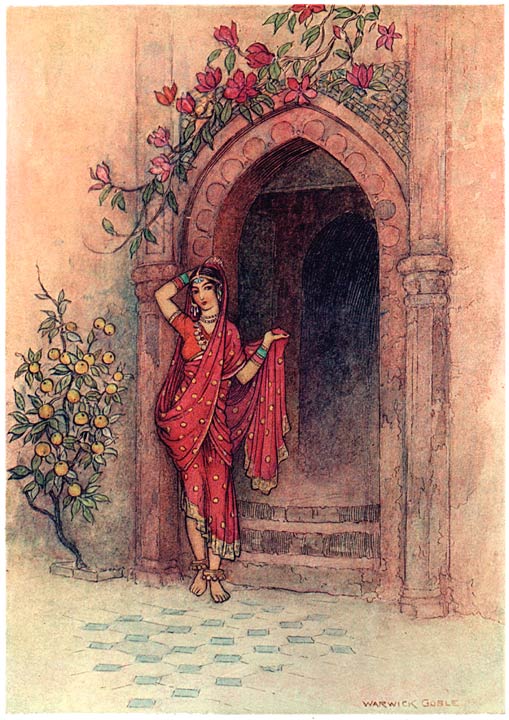

There was a poor half-witted Brahman who had a wife but no children. It was only with difficulty he could supply the wants of himself and his wife. And the worst of it was that he was rather lazily inclined. He was averse to taking long journeys, otherwise he might always have had enough, in the shape of presents from rich men, to enable him and his wife to live comfortably. There was at that time a king in a neighbouring country who was celebrating the funeral obsequies of his mother with great pomp. Brahmans and beggars were going from different parts with the expectation of receiving rich presents. Our Brahman was requested by his wife to seize this opportunity and get a little money; but his constitutional indolence stood in the way. The woman, however, gave her husband no rest till she extorted from him the promise that he would go. The good woman, accordingly, cut down a plantain tree and burnt it to ashes, with which ashes she cleaned the clothes of her husband, and made them as white as any fuller could make them. She did this because her husband was going to the palace of a great king, who could not be approached by men clothed in dirty rags; besides, as a Brahman, he was bound to appear neat and clean. The Brahman at last one morning left his house for the palace of the great king. As he was somewhat imbecile, he did not inquire of any one which road he should take; but he went on and on, and proceeded whithersoever his two eyes directed him. He was of course not on the right road, indeed he had reached a region where he did not meet with a single human being for many miles, and where he saw sights which he had never seen in his life. He saw hillocks of cowries (shells used as money) on the roadside: he had not proceeded far from them when he saw hillocks of pice, then successively hillocks of four-anna pieces, hillocks of eight-anna pieces, and hillocks of rupees. To the infinite surprise of the poor Brahman, these hillocks of shining silver coins were succeeded by a large hill of burnished gold-mohurs, which were all as bright as if they had been just issued from the mint. Close to this hill of gold-mohurs was a large house which seemed to be the palace of a powerful and rich king, at the door of which stood a lady of exquisite beauty. The lady, seeing the Brahman, said, “Come, my beloved husband; you married me when I was young, and you never came once after our marriage, though I have been daily expecting you. Blessed be this day which has made me see the face of my husband. Come, my sweet, come in, wash your feet and rest after the fatigues of your journey; eat and drink, and after that we shall make ourselves merry.” The Brahman was astonished beyond measure. He had no recollection of having been married in early youth to any other woman than the woman who was now keeping house with him. But being a Kulin Brahman, he thought it was quite possible that his father had got him married when he was a little child, though the fact had made no impression on his mind. But whether he remembered it or not, the fact was certain, for the woman declared that she was his wedded wife,—and such a wife! as beautiful as the goddesses of Indra’s heaven, and no doubt as wealthy as she was beautiful. While these thoughts were passing through the Brahman’s mind, the lady said again, “Are you doubting in your mind whether I am your wife? Is it possible that all recollection of that happy event has been effaced from your mind—all the pomp and circumstance of our nuptials? Come in, beloved; this is your own house, for whatever is mine is thine.” The Brahman succumbed to the loving entreaties of the fair lady, and went into the house. The house was not an ordinary one—it was a magnificent palace, all the apartments being large and lofty and richly furnished. But one thing surprised the Brahman very much, and that was that there was no other person in the house besides the lady herself. He could not account for so singular a phenomenon; neither could he explain how it was that he did not meet with any human being in his morning and evening walks. The fact was that the lady was not a human being. She was a Rakshasi. She had eaten up the king, the queen, and all the members of the royal family, and gradually all his subjects. This was the reason why human beings were not seen in those parts.

“At the door of which stood a lady of exquisite beauty”

The Rakshasi and the Brahman lived together for about a week, when the former said to the latter, “I am very anxious to see my sister, your other wife. You must go and fetch her, and we shall all live together happily in this large and beautiful house. You must go early to-morrow, and I will give you clothes and jewels for her.” Next morning the Brahman, furnished with fine clothes and costly ornaments, set out for his home. The poor woman was in great distress; all the Brahmans and Pandits that had been to the funeral ceremony of the king’s mother had returned home loaded with largesses; but her husband had not returned,—and no one could give any news of him, for no one had seen him there. The woman therefore concluded that he must have been murdered on the road by highwaymen. She was in this terrible suspense, when one day she heard a rumour in the village that her husband was seen coming home with fine clothes and costly jewels for his wife. And sure enough the Brahman soon appeared with his valuable load. On seeing his wife the Brahman thus accosted her:—“Come with me, my dearest wife; I have found my first wife. She lives in a stately palace, near which are hillocks of rupees and a large hill of gold-mohurs. Why should you pine away in wretchedness and misery in this horrible place? Come with me to the house of my first wife, and we shall all live together happily.” When the woman heard her husband speak of his first wife, of hillocks of rupees and of a hill of gold-mohurs, she thought in her mind that her half-witted good man had become quite mad; but when she saw the exquisitely beautiful silks and satins and the ornaments set with diamonds and precious stones, which only queens and princesses were in the habit of putting on, she concluded in her mind that her poor husband had fallen into the meshes of a Rakshasi. The Brahman, however, insisted on his wife’s going with him, and declared that if she did not come she was at liberty to pine away in poverty, but that for himself he meant to return forthwith to his first and rich wife. The good woman, after a great deal of altercation with her husband, resolved to go with him and judge for herself how matters stood. They set out accordingly the next morning, and went by the same road on which the Brahman had travelled. The woman was not a little surprised to see hillocks of cowries, of pice, of eight-anna pieces, of rupees, and last of all a lofty hill of gold-mohurs. She saw also an exceedingly beautiful lady coming out of the palace hard by, and hastening towards her. The lady fell on the neck of the Brahman woman, wept tears of joy, and said, “Welcome, beloved sister! this is the happiest day of my life! I have seen the face of my dearest sister!” The party then entered the palace.

What with the stately mansion in which he was lodged, with the most delectable provisions which seemed to rise as if by enchantment, what with the caresses and endearments of his two wives, the one human and the other demoniac, who vied with each other in making him happy and comfortable, the Brahman had a jolly time of it. He was steeped as it were in an ocean of enjoyment. Some fifteen or sixteen years were spent by the Brahman in this state of Elysian pleasure, during which period his two wives presented him with two sons. The Rakshasi’s son, who was the elder, and who looked more like a god than a human being, was named Sahasra Dal, literally the Thousand-Branched; and the son of the Brahman woman, who was a year younger, was named Champa Dal, that is, branch of a champaka tree. The two boys loved each other dearly. They were both sent to a school which was several miles distant, to which they used every day to go riding on two little ponies of extraordinary fleetness.

The Brahman woman had all along suspected from a thousand little circumstances that her sister-in-law was not a human being but a Rakshasi; but her suspicion had not yet ripened into certainty, for the Rakshasi exercised great self-restraint on herself, and never did anything which human beings did not do. But the demoniac nature, like murder, will out. The Brahman having nothing to do, in order to pass his time had recourse to hunting. The first day he returned from the hunt, he had bagged an antelope. The antelope was laid in the courtyard of the palace. At the sight of the antelope the mouth of the raw-eating Rakshasi began to water. Before the animal was dressed for the kitchen, she took it away into a room, and began devouring it. The Brahman woman, who was watching the whole scene from a secret place, saw her Rakshasi sister tear off a leg of the antelope, and opening her tremendous jaws, which seemed to her imagination to extend from earth to heaven, swallow it up. In this manner the body and other limbs of the antelope were devoured, till only a little bit of the meat was kept for the kitchen. The second day another antelope was bagged, and the third day another; and the Rakshasi, unable to restrain her appetite for raw flesh, devoured these two as she had devoured the first. On the third day the Brahman woman expressed to the Rakshasi her surprise at the disappearance of nearly the whole of the antelope with the exception of a little bit. The Rakshasi looked fierce and said, “Do I eat raw flesh?” To which the Brahman woman replied, “Perhaps you do, for aught I know to the contrary.” The Rakshasi, knowing herself to be discovered, looked fiercer than before, and vowed revenge. The Brahman woman concluded in her mind that the doom of herself, of her husband, and of her son was sealed. She spent a miserable night, believing that next day she would be killed and eaten up, and that her husband and son would share the same fate. Early next morning, before her son Champa Dal went to school, she gave him in a small golden vessel a little quantity of her own breast milk, and told him to be constantly watching its colour. “Should you,” she said, “see the milk get a little red, then conclude that your father has been killed; and should you see it grow still redder, then conclude that I am killed: when you see this, gallop away for your life as fast as your horse can carry you, for if you do not, you also will be devoured.”

The Rakshasi on getting up from bed—and she had prevented the Brahman overnight from having any communication with his wife—proposed that she and the Brahman should go to bathe in the river, which was at some distance. She would take no denial; the Brahman had therefore to follow her as meekly as a lamb. The Brahman woman at once saw from the proposal that ruin was impending; but it was beyond her power to avert the catastrophe. The Rakshasi, on the river-side, assuming her own proper gigantic dimensions, took hold of the ill-fated Brahman, tore him limb by limb, and devoured him up. She then ran to her house, and seized the Brahman woman, and put her into her capacious stomach, clothes, hair and all. Young Champa Dal, who, agreeably to his mother’s instructions, was diligently watching the milk in the small golden vessel, was horror-struck to find the milk redden a little. He set up a cry and said that his father was killed; a few minutes after, finding the milk become completely red, he cried yet louder, and rushing to his pony, mounted it. His half-brother, Sahasra Dal, surprised at Champa Dal’s conduct, said, “Where are you going, Champa? Why are you crying? Let me accompany you.” “Oh! do not come to me. Your mother has devoured my father and mother; don’t you come and devour me.” “I will not devour you; I’ll save you.” Scarcely had he uttered these words and galloped away after Champa Dal, when he saw his mother in her own Rakshasi form appearing at a distance, and demanding that Champa Dal should come to her. He said, “I will come to you, not Champa.” So saying, he went to his mother, and with his sword, which he always wore as a young prince, cut off her head.

Champa Dal had, in the meantime, galloped off a good distance, as he was running for his life; but Sahasra Dal, by pricking his horse repeatedly, soon overtook him, and told him that his mother was no more. This was small consolation to Champa Dal, as the Rakshasi, before being killed, had devoured both his father and mother; still he could not but feel that Sahasra Dal’s friendship was sincere. They both rode fast, and as their horses were of the breed of pakshirajes (literally, kings of birds), they travelled over hundreds of miles. An hour or two before sundown they descried a village, to which they made up, and became guests in the house of one of its most respectable inhabitants. The two friends found the members of that respectable family in deep gloom. Evidently there was something agitating them very much. Some of them held private consultations, and others were weeping. The eldest lady of the house, the mother of its head, said aloud, “Let me go, as I am the eldest. I have lived long enough; at the utmost my life would be cut short only by a year or two.” The youngest member of the house, who was a little girl, said, “Let me go, as I am young and useless to the family; if I die I shall not be missed.” The head of the house, the son of the old lady, said, “I am the head and representative of the family; it is but reasonable that I should give up my life.” His younger brother said, “You are the main prop and pillar of the family; if you go the whole family is ruined. It is not reasonable that you should go; let me go, as I shall not be much missed.” The two strangers listened to all this conversation with no little curiosity. They wondered what it all meant. Sahasra Dal at last, at the risk of being thought meddlesome, ventured to ask the head of the house the subject of their consultations, and the reason of the deep misery but too visible in their countenances and words. The head of the house gave the following answer: “Know then, worthy guests, that this part of the country is infested by a terrible Rakshasi, who has depopulated all the regions round. This town, too, would have been depopulated, but that our king became a suppliant before the Rakshasi, and begged her to show mercy to us his subjects. The Rakshasi replied, ‘I will consent to show mercy to you and to your subjects only on this condition, that you every night put a human being, either male or female, in a certain temple for me to feast upon. If I get a human being every night I will rest satisfied, and not commit any further depredations on your subjects.’ Our king had no other alternative than to agree to this condition, for what human beings can ever hope to contend against a Rakshasi? From that day the king made it a rule that every family in the town should in its turn send one of its members to the temple as a victim to appease the wrath and to satisfy the hunger of the terrible Rakshasi. All the families in this neighbourhood have had their turn, and this night it is the turn for one of us to devote himself to destruction. We are therefore discussing who should go. You must now perceive the cause of our distress.” The two friends consulted together for a few minutes, and at the conclusion of their consultations, Sahasra Dal, who was the spokesman of the party, said, “Most worthy host, do not any longer be sad: as you have been very kind to us, we have resolved to requite your hospitality by ourselves going to the temple and becoming the food of the Rakshasi. We go as your representatives.” The whole family protested against the proposal. They declared that guests were like gods, and that it was the duty of the host to endure all sorts of privation for the comfort of the guest, and not the duty of the guest to suffer for the host. But the two strangers insisted on standing proxy to the family, who, after a great deal of yea and nay, at last consented to the arrangement.

Immediately after candle-light, Sahasra Dal and Champa Dal, with their two horses, installed themselves in the temple, and shut the door. Sahasra told his brother to go to sleep, as he himself was determined to sit up the whole night and watch against the coming of the terrible Rakshasi. Champa was soon in a fine sleep, while Sahasra lay awake. Nothing happened during the early hours of the night, but no sooner had the gong of the king’s palace announced the dead hour of midnight than Sahasra heard the sound as of a rushing tempest, and immediately concluded, from his knowledge of Rakshasas, that the Rakshasi was nigh. A thundering knock was heard at the door, accompanied with the following words:—

“How, mow, khow!

A human being I smell;

Who watches inside?”

To this question Sahasra Dal made the following reply:—

“Sahasra Dal watcheth,

Champa Dal watcheth,

Two winged horses watch.”

On hearing this answer the Rakshasi turned away with a groan, knowing that Sahasra Dal had Rakshasa blood in his veins. An hour after, the Rakshasi returned, thundered at the door, and called out—

“How, mow, khow!

A human being I smell;

Who watcheth inside?”

Sahasra Dal again replied—

“Sahasra Dal watcheth,

Champa Dal watcheth,

Two winged horses watch.”

The Rakshasi again groaned and went away. At two o’clock and at three o’clock the Rakshasi again and again made her appearance, and made the usual inquiry, and obtaining the same answer, went away with a groan. After three o’clock, however, Sahasra Dal felt very sleepy: he could not any longer keep awake. He therefore roused Champa, told him to watch, and strictly enjoined upon him, in reply to the query of the Rakshasi, to mention Sahasra’s name first. With these instructions he went to sleep. At four o’clock the Rakshasi again made her appearance, thundered at the door, and said—

“How, mow, khow!

A human being I smell;

Who watches inside?”

As Champa Dal was in a terrible fright, he forgot the instructions of his brother for the moment, and answered—

“Champa Dal watcheth,

Sahasra Dal watcheth,

Two winged horses watch.”

On hearing this reply the Rakshasi uttered a shout of exultation, laughed such a laugh as only demons can, and with a dreadful noise broke open the door. The noise roused Sahasra, who in a moment sprung to his feet, and with his sword, which was as supple as a palm-leaf, cut off the head of the Rakshasi. The huge mountain of a body fell to the ground, making a great noise, and lay covering many an acre. Sahasra Dal kept the severed head of the Rakshasi near him, and went to sleep. Early in the morning some wood-cutters, who were passing near the temple, saw the huge body on the ground. They could not from a distance make out what it was, but on coming near they knew that it was the carcase of the terrible Rakshasi, who had by her voracity nearly depopulated the country. Remembering the promise made by the king that the killer of the Rakshasi should be rewarded by the hand of his daughter and with a share of the kingdom, each of the wood-cutters, seeing no claimant at hand, thought of obtaining the reward. Accordingly each of them cut off a part of a limb of the huge carcase, went to the king, and represented himself to be the destroyer of the great raw-eater, and claimed the reward. The king, in order to find out the real hero and deliverer, inquired of his minister the name of the family whose turn it was on the preceding night to offer a victim to the Rakshasi. The head of that family, on being brought before the king, related how two youthful travellers, who were guests in his house, volunteered to go into the temple in the room of a member of his family. The door of the temple was broken open; Sahasra Dal and Champa Dal and their horses were found all safe; and the head of the Rakshasi, which was with them, proved beyond the shadow of a doubt that they had killed the monster. The king kept his word. He gave his daughter in marriage to Sahasra Dal and the sovereignty of half his dominions. Champa Dal remained with his friend in the king’s palace, and rejoiced in his prosperity.

Sahasra Dal and Champa Dal lived together happily for some time, when a misunderstanding arose between them in this wise. There was in the service of the queen-mother a certain maid-servant who was the most useful domestic in the palace. There was nothing which she could not put her hands to and perform. She had uncommon strength for a woman; neither was her intelligence of a mean order. She was a woman of immense activity and energy; and if she were absent one day from the palace, the affairs of the zenana would be in perfect disorder. Hence her services were highly valued by the queen-mother and all the ladies of the palace. But this woman was not a woman; she was a Rakshasi, who had put on the appearance of a woman to serve some purposes of her own, and then taken service in the royal household. At night, when every one in the palace was asleep, she used to assume her own real form, and go about in quest of food, for the quantity of food that is sufficient for either man or woman was not sufficient for a Rakshasi. Now Champa Dal, having no wife, was in the habit of sleeping outside the zenana, and not far from the outer gate of the palace. He had noticed her going about on the premises and devouring sundry goats and sheep, horses and elephants. The maid-servant, finding that Champa Dal was in the way of her supper, determined to get rid of him. She accordingly went one day to the queen-mother, and said, “Queen-mother! I am unable any longer to work in the palace.” “Why? what is the matter, Dasi?2 How can I get on without you? Tell me your reasons. What ails you?” “Why,” said the woman, “nowadays it is impossible for a poor woman like me to preserve my honour in the palace. There is that Champa Dal, the friend of your son-in-law; he always cracks indecent jokes with me. It is better for me to beg for my rice than to lose my honour. If Champa Dal remains in the palace I must go away.” As the maid-servant was an absolute necessity in the palace, the queen-mother resolved to sacrifice Champa Dal to her. She therefore told Sahasra Dal that Champa Dal was a bad man, that his character was loose, and that therefore he must leave the palace. Sahasra Dal earnestly pleaded on behalf of his friend, but in vain; the queen-mother had made up her mind to drive him out of the palace. Sahasra Dal had not the courage to speak personally to his friend on the subject; he therefore wrote a letter to him, in which he simply said that for certain reasons Champa must leave the palace immediately. The letter was put in his room after he had gone to bathe. On reading the letter Champa Dal, exceedingly grieved, mounted his fleet horse and left the palace.

“In a trice she woke up, sat up in her bed, and eyeing the stranger, inquired who he was”

As Champa’s horse was uncommonly fleet, in a few hours he traversed thousands of miles, and at last found himself at the gateway of what seemed a magnificent palace. Dismounting from his horse, he entered the house, where he did not meet with a single creature. He went from apartment to apartment, but though they were all richly furnished he did not see a single human being. At last, in one of the side rooms, he found a young lady of heavenly beauty lying down on a splendid bedstead. She was asleep. Champa Dal looked upon the sleeping beauty with rapture—he had not seen any woman so beautiful. Upon the bed, near the head of the young lady, were two sticks, one of silver and the other of gold. Champa took the silver stick into his hand, and touched with it the body of the lady; but no change was perceptible. He then took up the gold stick and laid it upon the lady, when in a trice she woke up, sat in her bed, and eyeing the stranger, inquired who he was. Champa Dal briefly told his story. The young lady, or rather princess—for she was nothing less—said, “Unhappy man! why have you come here? This is the country of Rakshasas, and in this house and round about there live no less than seven hundred Rakshasas. They all go away to the other side of the ocean every morning in search of provisions; and they all return every evening before dusk. My father was formerly king in these regions, and had millions of subjects, who lived in flourishing towns and cities. But some years ago the invasion of the Rakshasas took place, and they devoured all his subjects, and himself and my mother, and my brothers and sisters. They devoured also all the cattle of the country. There is no living human being in these regions excepting myself; and I too should long ago have been devoured had not an old Rakshasi, conceiving strange affection for me, prevented the other Rakshasas from eating me up. You see those sticks of silver and gold; the old Rakshasi, when she goes away in the morning, kills me with the silver stick, and on her return in the evening re-animates me with the gold stick. I do not know how to advise you; if the Rakshasas see you, you are a dead man.” Then they both talked to each other in a very affectionate manner, and laid their heads together to devise if possible some means of escape from the hands of the Rakshasas. The hour of the return of the seven hundred raw-eaters was fast approaching; and Keshavati—for that was the name of the princess, so called from the abundance of her hair—told Champa to hide himself in the heaps of the sacred trefoil which were lying in the temple of Siva in the central part of the palace. Before Champa went to his place of concealment, he touched Keshavati with the silver stick, on which she instantly died.

Shortly after sunset Champa Dal heard from beneath the heaps of the sacred trefoil the sound as of a mighty rushing wind. Presently he heard terrible noises in the palace. The Rakshasas had come home from cruising, after having filled their stomachs, each one, with sundry goats, sheep, cows, horses, buffaloes, and elephants. The old Rakshasi, of whom we have already spoken, came to Keshavati’s room, roused her by touching her body with the gold stick, and said—

“Hye, mye, khye!

A human being I smell.”

On which Keshavati said, “I am the only human being here; eat me if you like.” To which the raw-eater replied, “Let me eat up your enemies; why should I eat you?” She laid herself down on the ground, as long and as high as the Vindhya Hills, and presently fell asleep. The other Rakshasas and Rakshasis also soon fell asleep, being all tired out on account of their gigantic labours in the day. Keshavati also composed herself to sleep; while Champa, not daring to come out of the heaps of leaves, tried his best to court the god of repose. At daybreak all the raw-eaters, seven hundred in number, got up and went as usual to their hunting and predatory excursions, and along with them went the old Rakshasi, after touching Keshavati with the silver stick. When Champa Dal saw that the coast was clear, he came out of the temple, walked into Keshavati’s room, and touched her with the gold stick, on which she woke up. They sauntered about in the gardens, enjoying the cool breeze of the morning; they bathed in a lucid tank which was in the grounds; they ate and drank, and spent the day in sweet converse. They concocted a plan for their deliverance. They settled that Keshavati should ask the old Rakshasi on what the life of a Rakshasa depended, and when the secret should be made known they would adopt measures accordingly. As on the preceding evening, Champa, after touching his fair friend with the silver stick, took refuge in the temple beneath the heaps of the sacred trefoil. At dusk the Rakshasas as usual came home; and the old Rakshasi, rousing her pet, said—

“Hye, mye, khye!

A human being I smell.”

Keshavati answered, “What other human being is here excepting myself? Eat me up, if you like.” “Why should I eat you, my darling? Let me eat up all your enemies.” Then she laid down on the ground her huge body, which looked like a part of the Himalaya mountains. Keshavati, with a phial of heated mustard oil, went towards the feet of the Rakshasi, and said, “Mother, your feet are sore with walking; let me rub them with oil.” So saying, she began to rub with oil the Rakshasi’s feet; and while she was in the act of doing so, a few tear-drops from her eyes fell on the monster’s leg. The Rakshasi smacked the tear-drops with her lips, and finding the taste briny, said, “Why are you weeping, darling? What aileth thee?” To which the princess replied, “Mother, I am weeping because you are old, and when you die I shall certainly be devoured by one of the Rakshasas.” “When I die! Know, foolish girl, that we Rakshasas never die. We are not naturally immortal, but our life depends on a secret which no human being can unravel. Let me tell you what it is that you may be comforted. You know yonder tank; there is in the middle of it a Sphatikasthambha, on the top of which in deep waters are two bees. If any human being can dive into the waters, and bring up to land the two bees from the pillar in one breath, and destroy them so that not a drop of their blood falls to the ground, then we Rakshasas shall certainly die; but if a single drop of blood falls to the ground, then from it will start up a thousand Rakshasas. But what human being will find out this secret, or, finding it, will be able to achieve the feat? You need not, therefore, darling, be sad; I am practically immortal.” Keshavati treasured up the secret in her memory, and went to sleep.

Early next morning the Rakshasas as usual went away; Champa came out of his hiding-place, roused Keshavati, and fell a-talking. The princess told him the secret she had learnt from the Rakshasi. Champa immediately made preparations for accomplishing the mighty deed. He brought to the side of the tank a knife and a quantity of ashes. He disrobed himself, put a drop or two of mustard oil into each of his ears to prevent water from entering in, and dived into the waters. In a moment he got to the top of the crystal pillar in the middle of the tank, caught hold of the two bees he found there, and came up in one breath. Taking the knife, he cut up the bees over the ashes, a drop or two of the blood fell, not on the ground, but on the ashes. When Champa caught hold of the bees, a terrible scream was heard at a distance. This was the wailing of the Rakshasas, who were all running home to prevent the bees from being killed; but before they could reach the palace, the bees had perished. The moment the bees were killed, all the Rakshasas died, and their carcases fell on the very spot on which they were standing. Champa and the princess afterwards found that the gateway of the palace was blocked up by the huge carcases of the Rakshasas—some of them having nearly succeeded in getting to the palace. In this manner was effected the destruction of the seven hundred Rakshasas.

After the destruction of the seven hundred raw-eating monsters, Champa Dal and Keshavati got married together by the exchange of garlands of flowers. The princess, who had never been out of the house, naturally expressed a desire to see the outer world. They used every day to take long walks both morning and evening, and as a large river was hard by Keshavati wished to bathe in it. The first day they went to bathe, one of Keshavati’s hairs came off, and as it is the custom with women never to throw away a hair unaccompanied with something else, she tied the hair to a shell which was floating on the water; after which they returned home. In the meantime the shell with the hair tied to it floated down the stream, and in course of time reached that ghat4 at which Sahasra Dal and his companions were in the habit of performing their ablutions. The shell passed by when Sahasra Dal and his friends were bathing; and he, seeing it at some distance, said to them, “Whoever succeeds in catching hold of yonder shell shall be rewarded with a hundred rupees.” They all swam towards it, and Sahasra Dal, being the fleetest swimmer, got it. On examining it he found a hair tied to it. But such hair! He had never seen so long a hair. It was exactly seven cubits long. “The owner of this hair must be a remarkable woman, and I must see her”—such was the resolution of Sahasra Dal. He went home from the river in a pensive mood, and instead of proceeding to the zenana for breakfast, remained in the outer part of the palace. The queen-mother, on hearing that Sahasra Dal was looking melancholy and had not come to breakfast, went to him and asked the reason. He showed her the hair, and said he must see the woman whose head it had adorned. The queen-mother said, “Very well, you shall have that lady in the palace as soon as possible. I promise you to bring her here.” The queen-mother told her favourite maid-servant, whom she knew to be full of resources—the same who was a Rakshasi in disguise—that she must, as soon as possible, bring to the palace that lady who was the owner of the hair seven cubits long. The maid-servant said she would be quite able to fetch her. By her directions a boat was built of Hajol wood, the oars of which were of Mon Paban wood. The boat was launched on the stream, and she went on board of it with some baskets of wicker-work of curious workmanship; she also took with her some sweetmeats into which some poison had been mixed. She snapped her fingers thrice, and uttered the following charm:—

“Boat of Hajol!

Oars of Mon Paban!

Take me to the Ghat,

In which Keshavati bathes.”

No sooner had the words been uttered than the boat flew like lightning over the waters. It went on and on, leaving behind many a town and city. At last it stopped at a bathing-place, which the Rakshasi maid-servant concluded was the bathing ghat of Keshavati. She landed with the sweetmeats in her hand. She went to the gate of the palace, and cried aloud, “O Keshavati! Keshavati! I am your aunt, your mother’s sister. I am come to see you, my darling, after so many years. Are you in, Keshavati?” The princess, on hearing these words, came out of her room, and making no doubt that she was her aunt, embraced and kissed her. They both wept rivers of joy—at least the Rakshasi maid-servant did, and Keshavati followed suit through sympathy. Champa Dal also thought that she was the aunt of his newly married wife. They all ate and drank and took rest in the middle of the day. Champa Dal, as was his habit, went to sleep after breakfast. Towards afternoon, the supposed aunt said to Keshavati, “Let us both go to the river and wash ourselves.” Keshavati replied, “How can we go now? my husband is sleeping.” “Never mind,” said the aunt, “let him sleep on; let me put these sweetmeats, that I have brought, near his bedside, that he may eat them when he gets up.” They then went to the river-side close to the spot where the boat was. Keshavati, when she saw from some distance the baskets of wicker-work in the boat, said, “Aunt, what beautiful things are those! I wish I could get some of them.” “Come, my child, come and look at them; and you can have as many as you like.” Keshavati at first refused to go into the boat, but on being pressed by her aunt, she went. The moment they two were on board, the aunt snapped her fingers thrice and said:—

“Boat of Hajol!

Oars of Mon Paban!

Take me to the Ghat,

In which Sahasra Dal bathes.”

As soon as these magical words were uttered the boat moved and flew like an arrow over the waters. Keshavati was frightened and began to cry, but the boat went on and on, leaving behind many towns and cities, and in a trice reached the ghat where Sahasra Dal was in the habit of bathing. Keshavati was taken to the palace; Sahasra Dal admired her beauty and the length of her hair; and the ladies of the palace tried their best to comfort her. But she set up a loud cry, and wanted to be taken back to her husband. At last when she saw that she was a captive, she told the ladies of the palace that she had taken a vow that she would not see the face of any strange man for six months. She was then lodged apart from the rest in a small house, the window of which overlooked the road; there she spent the livelong day and also the livelong night—for she had very little sleep—in sighing and weeping.

In the meantime when Champa Dal awoke from sleep, he was distracted with grief at not finding his wife. He now thought that the woman, who pretended to be his wife’s aunt, was a cheat and an impostor, and that she must have carried away Keshavati. He did not eat the sweetmeats, suspecting they might be poisoned. He threw one of them to a crow which, the moment it ate it, dropped down dead. He was now the more confirmed in his unfavourable opinion of the pretended aunt. Maddened with grief, he rushed out of the house, and determined to go whithersoever his eyes might lead him. Like a madman, always blubbering “O Keshavati! O Keshavati!” he travelled on foot day after day, not knowing whither he went. Six months were spent in this wearisome travelling when, at the end of that period, he reached the capital of Sahasra Dal. He was passing by the palace-gate when the sighs and wailings of a woman sitting at the window of a house, on the road-side, attracted his attention. One moment’s look, and they recognised each other. They continued to hold secret communications. Champa Dal heard everything, including the story of her vow, the period of which was to terminate the following day. It is customary, on the fulfilment of a vow, for some learned Brahman to make public recitations of events connected with the vow and the person who makes it. It was settled that Champa Dal should take upon himself the functions of the reciter. Accordingly, next morning, when it was proclaimed by beat of drum that the king wanted a learned Brahman who could recite the story of Keshavati on the fulfilment of her vow, Champa Dal touched the drum and said that he would make the recitation. Next morning a gorgeous assembly was held in the courtyard of the palace under a huge canopy of silk. The old king, Sahasra Dal, all the courtiers and the learned Brahmans of the country, were present there. Keshavati was also there behind a screen that she might not be exposed to the rude gaze of the people. Champa Dal, the reciter, sitting on a dais, began the story of Keshavati, as we have related it, from the beginning, commencing with the words—“There was a poor and half-witted Brahman, etc.” As he was going on with the story, the reciter every now and then asked Keshavati behind the screen whether the story was correct; to which question she as often replied, “Quite correct; go on, Brahman.” During the recitation of the story the Rakshasi maid-servant grew pale, as she perceived that her real character was discovered; and Sahasra Dal was astonished at the knowledge of the reciter regarding the history of his own life. The moment the story was finished, Sahasra Dal jumped up from his seat, and embracing the reciter, said, “You can be none other than my brother Champa Dal.” Then the prince, inflamed with rage, ordered the maid-servant into his presence. A large hole, as deep as the height of a man, was dug in the ground; the maid-servant was put into it in a standing posture; prickly thorn was heaped around her up to the crown of her head: in this wise was the maid-servant buried alive. After this Sahasra Dal and his princess, and Champa Dal and Keshavati, lived happily together many years.

Thus my story endeth,

The Natiya-thorn withereth, etc.

If you liked this story, leave me a comment down below. Join our Facebook community. And don’t forget to Subscribe!

Enjoy other folk tales from India!