St. Nicholas – His Legend and His Role in the Christmas Celebration and Other Popular Customs (By George H. McKnight, 1917) – Chapter 5

THE BOY BISHOP, OR NICHOLAS BISHOP

In all the representations of St. Nicholas, painting or image, except those pictures dealing with his childhood, he appears with the robes and insignia of a bishop. St. Nicholas is preëminently the bishop-saint. Concerning his boyhood elevation to the episcopal rank, legend has an interesting story to relate. Once more let us turn to the Golden Legend, which relates the story as follows:

After this the bishop of Mirea died and other bishops assembled for to purvey to this church a bishop. And there was, among the others, a bishop of great authority, and all the election was in him. And when he had warned all for to be in fastings and in prayers, this bishop heard that night a voice which said to him that, at the hour of matins, he should take heed to the doors of the church, and him that should come first to the church, and have the name of Nicholas they should sacre him bishop. And he showed this to the other bishops and admonished them for to be all in prayers; and he kept the doors. And this was a marvelous thing, for at the hour of matins, like as he had been sent from God, Nicholas arose tofore all other. And the bishop took him when he was come and demanded of him his name. And he, which was simple as a dove, inclined his head, and said: I have to name Nicholas. Then the bishop said to him: Nicholas, Servant and friend of God, for your holiness ye shall be bishop of this place. And sith they brought him to the church, howbeit that he refused it strongly, yet they set him in the chair. And he followed, as he did tofore in all things, in humility and honesty of manners. He woke in prayer and made his body lean, he eschewed company of women, he was humble in receiving all things, profitable in speaking, joyous in admonishing, and cruel in correcting.

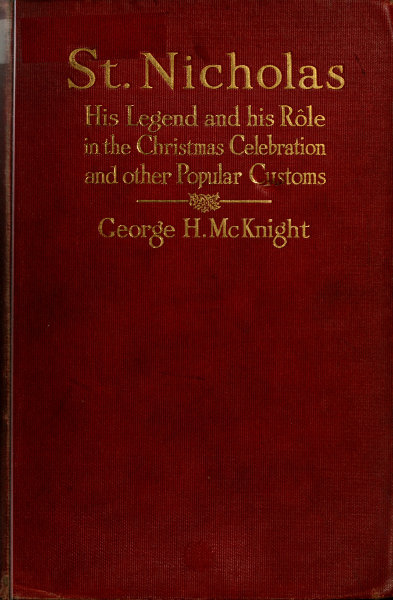

This episode is the most celebrated in the life of St. Nicholas. It is represented in a number of Italian paintings. The early morning appearance of the boy Nicholas at the church and his surprise as he learns of his election are presented in particularly lively manner in one of the scenes from his life by Lorenzetti preserved at Florence.

Interesting in itself, the story of the elevation of the boy Nicholas to the rank of bishop also possesses interest because associated with some of the most interesting of early church customs, those centering about the personage of the Boy Bishop, or Nicholas Bishop as he was sometimes called. The explanation of this interesting personage and the customs associated with him, like that of Santa Claus, is a complex one. In the case of the Boy Bishop customs once more we have probably to do with the survival of pre-Christian customs with which the Church associated new names and new meaning.

The spirit that dominated the Christian December celebration and many details of the external form of celebration are to be found in the Roman pagan customs of December and early January. The early winter season in Roman times was a period of general relaxation and merry making. In the week beginning December 17th and ending December 23d, the ancient god Saturn resumed once more, for a limited period, the benign rule of which he had been deprived by his more strenuous, shall we say more efficient, son Jove. The week of the rule of Saturn, the Saturnalia, was a time of revelry and riot. The serious was barred. No business was allowed; drinking and games and noise prevailed. All men were to be equal, rich and poor, slave and free. There was chosen a mock king who could impose forfeits. The Roman New Year’s feast had a similar character. As at the Saturnalia, masters drank and gambled with slaves. In the words of the Greek sophist, Libanius: “From the minds of young people it (the New Year’s feast) removes two kinds of dread: the dread of the schoolmaster and the dread of the stern pedagogue.”

A. Lorenzetti. The Boy Nicholas Indicated as the Divine Choice for Bishop.

The attitude of the Christian church toward pagan custom is well known. Since it could not hope to extirpate old practice, it endeavored to adapt it to Christian use, giving to it Christian meaning and, as far as possible, Christian character. It aimed to make the birth of Christ, and the associated events, the dominating idea in its celebration at the beginning of winter. In spite of this intention, in the popular customs of the Christmas season, even in the ceremonies of the Church, there is apparent a survival of many features of pagan practice. Especially in the practice of the week following Christmas, there is to be observed the leveling or inversion of rank, the election of a mock ruler, and the general relaxation of discipline that were features of the pagan celebrations of the same season at Rome. Thus in the three days immediately following Christmas, church discipline was sufficiently relaxed to permit of revels in turn, by the lower orders of clergy and by the choir boys. December 26th, St. Stephen’s day, was the day for the deacons, since St. Stephen was a deacon. For this day the deacons supplanted the higher dignitaries and took the preëminence in the divine services. On Christmas night, the eve of St. Stephen’s day, after vespers, the deacons formed a pompous procession dressed in silk copes like priests. On St. Stephen’s day the deacons performed the parts of the divine service. There was also a great deal of mock ceremonial, and drinking and processions in the streets, with visiting of houses and levying of contributions. On the following day, the day of St. John the Evangelist, the priests had their innings. Features of their celebration were mock blessings and the proclamation of a ribald form of indulgence. On the eve of Innocents’ day (Dec. 28th), the priests gave way to the choir boys, “the children,” for the celebration of Childermas. On Circumcision Day (Jan. 1st), the sub-deacons, the “rookies” among the priestly orders, took their turn at occupying the places of the higher clergy.

The day of the sub-deacons, possibly because of its coincidence with the Roman Kalends, was celebrated in a particularly mad fashion. In the words “Deposuit potentes de sede: et exaltavit humiles” sung in the Magnificat at Vespers, was found the suggestion for a general inversion in rank. For the time, the places of rank and honor were taken by the lowly sub-deacons. The sacred services were burlesqued in most shocking fashion varying in different places. In Paris in the fifteenth century, “priests danced in the choir dressed as women, panders, or minstrels. Wanton songs were sung. Black puddings were eaten at the horn of the altar while mass was being celebrated, and the altar was censed with ashes or by the smoke from the soles of old shoes.” Performers without the church were even more irreverent and riotous in character.

The choir boy customs of Holy Innocents’ day were somewhat like those described, although more restrained in character, since, as Mr. Chambers has remarked, boys were more amenable to discipline than the older clergy. There was a similar inversion of rank and, within limit, a similar burlesque of custom, on this day the choir boys taking precedence in rank, presided over by one of their number, usually elected on St. Nicholas’ day, with the title of Boy Bishop, or Nicholas Bishop.

A central feature of the celebration was a pompous church procession following vespers on Childermas eve. In this procession the inversion of rank was a feature. The book, the censer, and the candles, usually borne by boys, on this occasion were borne by reverend canons, and when at the end of the ceremony the procession returned to the choir, the boys took the places of dignity in the higher stalls, with the Boy Bishop in the stall of the bishop or dean. Then followed a feature doubtless in the estimation of the boys not less important than the procession, namely a supper provided by one of the church dignitaries.

On Innocents’ day all the services, including the Mass, were performed by the boys with their “Bishop,” also in many places the “Bishop” preached a sermon. Nor were the honor and dignity of the Boy Bishop confined to the ceremonies within the church. In mounted procession, with attendant boy prebends, he visited other religious houses and houses of neighboring people of prominence, singing songs and imparting blessings in the expectation of festal entertainment and of money gifts as well. In the year 1555 the “chylde byshope” of St. Paul’s with his company visited Queen Mary at St. James’s and sang a song before her both on St. Nicholas’ day (Dec. 6th) and on Innocents’ day (Dec. 28th). The amounts collected on these occasions were considerable. Robert de Holme,who was “Bishop” at York, received from the choirmaster, who served as treasurer, in 1369, the sum of £3 15s. 1-1/2d. But this was only a part of the receipts, for at intervals during the fortnight following Christmas, the “Bishop” with his troupe made trips in the neighborhood which netted handsome profit, the countess of Northumberland alone contributing twenty shillings and a gold ring. In Aberdeen the master of the grammar school was paid by a collection taken when he went the rounds with the “Bishop.” That this source of revenue was not a matter of trivial importance may be inferred from the interesting statement in the municipal registers that “he hes na uder fee to leif on.”

Some interesting details regarding French observance of the Boy Bishop custom have been garnered by Mr. Chambers from the records for Toul. At that place

the expenses of the feast, with the exception of the dinner on the day after Innocents’ day, which came out of the disciplinary fines, are assigned by the statutes to the canons in the order of their appointment. The responsible canon must give a supper on Innocents’ day, and on the following day a dessert out of what is over. He must also provide the “Bishop” with a horse, gloves, and a biretta when he rides abroad. At the supper a curious ceremony took place. The canon returned thanks to the “Bishop,” apologized for any shortcomings in the preparations, and finally handed the “Bishop” a cap of rosemary or other flowers, which was then conferred upon the canon to whose lot it would fall to provide the feast for the next anniversary. Should the canon disregard his duties the boys and sub-deacons were entitled to hang up a black cope on a candlestick in the middle of the choir in illius vituperium for as long as they might choose.

The elaborateness, too, of the manner of celebration, as well as the constant association with St. Nicholas, may be inferred from the following Northumberland inventory of robes and ornaments belonging to one of these Boy Bishops:

Imprimis, i. myter, well garnished with perle and precious stones, with nowches of silver and gilt before and behind. Item, iiii. rynges of silver and gilt, with four ridde precious stones in them. Item, i. pontifical with silver and gilt, with a blue stone in hytt. Item, i. owche, broken, silver and gilt, with iiii. precious stones, and a perle in the mydds. Item, a croose, with a staff of coper and gilt, with the ymage of St. Nicolas in the mydds. Item, i. vestment, redde, with lyons, with silver, with brydds of gold in the orferes of the same. Item, i. albe to the same, with starres in the paro. Item, i. white cope, stayned with tristells and orferes, redde sylke, with does of gold, and whytt napkins about the necks. Item, iiii. copes, blew sylk with red orferes, trayled, with whitt braunchis and flowers. Item, i. steyned cloth of the ymage of St. Nicholas. Item, i. taberd of skarlet, and a hodde thereto lyned with whitt sylk. Item, a hode of skarlett, lyned with blue sylk.

The earliest known reference to the Boy Bishop custom is from St. Gall in the year 911. King Conrad I. was visiting Bishop Solomon of Constance and heard so much of the Vespers procession at St. Gall that he determined to visit the monastery at the time of the revels. He found it “all very amusing and especially the procession of children, so grave and sedate that even when Conrad bade his train roll apples along the aisle, they did not budge.” In later years the custom lost much of its early sobriety, although doubtless a great deal of dignity, real or assumed, persisted in the church procession. The custom pervaded most of the countries of Europe in the following centuries.

In France it was not abolished until 1721. At Mainz, in Germany, it was not wholly extinct in 1779. In Belgium in the nineteenth century there survived a number of popular customs showing for the celebration of Innocents’ day of the present the same kind of inversion of authority that characterized the Boy Bishop customs of earlier times. Innocents’ day is in Belgium more than in other countries a popular festival, making up somewhat for the fact that in Belgium, Christmas is less of a children’s celebration than in other Teutonic countries, or perhaps owing to the greater importance of St. Nicholas customs in the Netherlands than in other countries. In any event, in Belgium, Innocents’ day is a real children’s festival: children are masters in the house, and parents must obey them. At Antwerp, in Brabant, and in some parts of the county of Limbourg, little boys and girls dress up for the day as papas and mammas. Usually the youngest of the family receives the key to the pantry and orders in the kitchen the meals for the day.

In England the Boy Bishop custom, which came to an end in the sixteenth century under Reformation influence, once prevailed throughout the length and breadth of the land—at first in cathedrals, collegiate churches, and schools, later “in every parish church where there was a sufficient band of choristers to furnish forth the Boy Bishop ceremonial, or sufficiently well-to-do parishioners to be worth laying under contribution.”

The relation of the Boy Bishop to St. Nicholas customs offers a number of difficulties to explain. Mr. Chambers leans to the view that the custom was originally associated with St. Nicholas’ day, an opinion supported by the fact that the “Bishop” was elected on the eve of St. Nicholas. But he believes that, like other St. Nicholas customs, the Santa Claus custom for instance, it was later transferred to the Christmas season. Something, however, may be said for a contrary explanation. It is an established fact that medieval schools and universities had their origin in the song schools of the Church; consequently in schools and universities there survived customs originally appropriate only to choir boys. In this way might be transferred a custom observed by choir boys on the festival at Holy Innocents’ day (Dec. 28th), to St. Nicholas’ day (Dec. 6th), the festival day of schoolboys, and the Boy Bishop of Innocents’ day get the name of Episcopus Nicholatensis, “Nicholas Bishop,” or by an admirable Latin pun at Eton, “Episcopus Nihilensis,” “Bishop of Nothing.” There is evident relationship between the custom of the Boy Bishop and the story of St. Nicholas elected bishop when a boy. Did the custom grow out of the story, or as is so often the case, did the story originate as an explanation of an established custom?

Oliver Wendell Holmes, on the occasion of a visit paid, late in life, to Westminster Abbey, singles out from “amidst all the imposing recollections of the ancient edifice,” one that impressed him “in the inverse ratio of its importance, … the little holes in the stones, in one place, where the boys of the choir used to play marbles.” In a similar way it may be remarked that among all the magnificent ceremonies in the history of the Church, few are more impressive than those associated with the Boy Bishop, or Nicholas Bishop. The choir boy, exercising his rule over his fellow boys, riding with them in parade about the city or surrounding country, or for the nonce lording it over his pompous superiors and indulging in playful parody of the ceremonies in which throughout the year he has taken a not always too patient part,—all this affords us a glimpse at natural boy nature centuries ago.